Hollow Ash

The story of building a home

Finding Hollow Ash

Dusk was closing in as we drove through the lanes west of Ross-on-Wye, on yet another house-hunting trip. We had just given up looking for a run-down cottage on The Doward, a wooded hill above the river Wye – and also above the A40 trunk road to South Wales. Because of the continual drone of traffic we cut short our search in the hope of finding another site before dark.

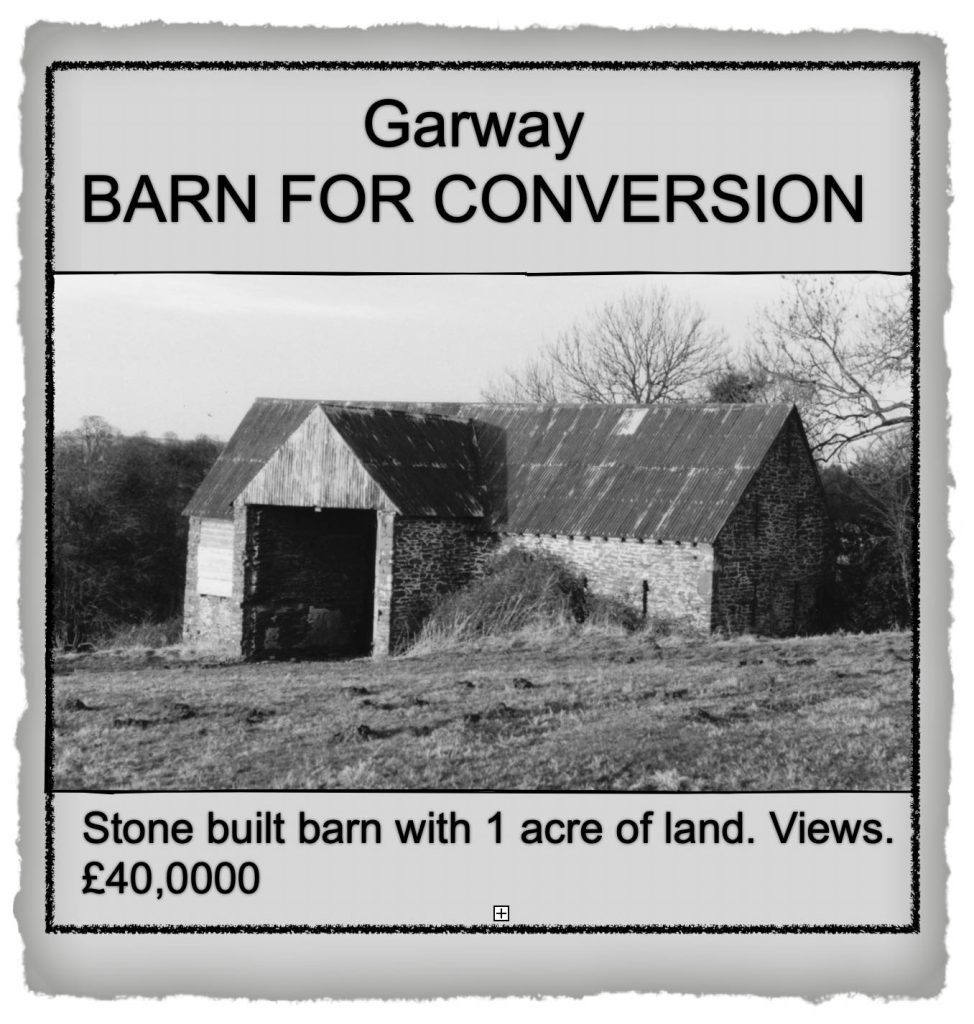

Clare had been excited by the postage stamp-sized, grainy black and white picture in the Property Pages picked up in Ross; more excited by this than by any of the other places visited (with the exception of the derelict half-timbered farmhouse, complete with one acre of apple orchard and cider press, overlooking the Wye at Kings Capel, but which had a price tag of £80,000). With the advert in one hand and directions in the other she navigated us through the network of lanes into the hills north of Monmouth.

As we turned into the farm track as directed by the ‘For Sale’ board which was still just visible I wondered whether this track would become familiar to me in the years to come as the last leg of my journey home. We stopped the car in front of the barn and got out. The first and overwhelming impression was of space and tranquility. With our backs to the barn we looked down into the Monnow Valley, held in a perfect composition by hills on each side, and the distant and familiar outlines of The Sugarloaf and The Skirrid in the centre. And what struck us both was that, as dusk turned to night, in that whole view contained not one street light.

In those few moments I think we both felt we could be settled there, although we said nothing of that to each other. So without even looking at the barn or the land, without the benefit of daylight, having met no locals nor enquired of the local amenities, we felt at ease in the place. That belief in the location gave us the strength to pull through the trials of the next few years.

That was November 4th, 1993. And now, from the other side of those hard years we are enjoying the tranquility, the darkness and the view from what has become our home – “Hollow Ash”.

Why move house?

Moving home, a notoriously stressful life experience, is not to be taken on lightly. So what was it that led to our decision?

We were living in a victorian end-of-terrace house in Stroud, Gloucestershire. As with most houses many things were far from ideal but we adapted and compromised, making the best of the opportunities. The house was in walking distance of the town centre and overlooked the attractive Slad Valley. We divided the steep, long and narrow garden into distinct areas: arbour, tiny lawn, compost, vegetables and fruit, pond, greenhouse and chicken run. We took on an allotment ¼ mile away. The basement floor included workshop space. It was a comfortable home and provided all our needs.

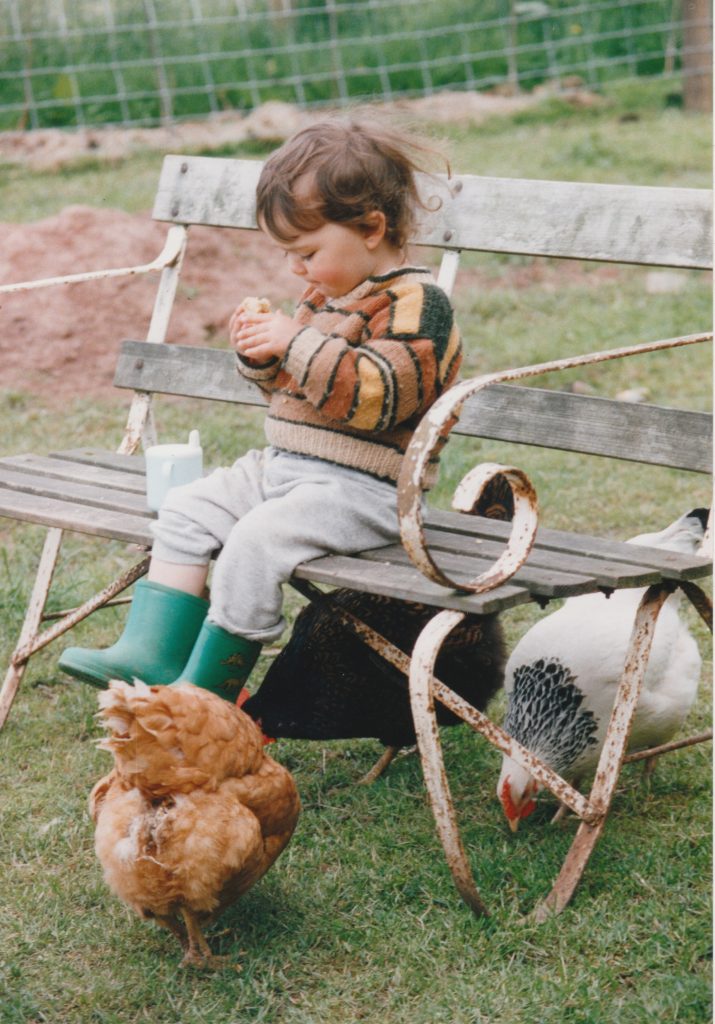

And yet… with a young family (Rosie 2½, Adam 6 months) our attention was focussed firmly on the future. I couldn’t see us growing old there and still being contented. Perhaps I sensed the mid-life crisis looming; maybe during the long, grey winters pushing a buggy up the hill from town, dodging broken glass and worse, Stroud began to lose its attraction; surely there was more to a “green” life than growing vegetables and trips to the recycling centre; was it worth putting so much money and energy into an old, damp, cheaply built and cheaply extended property?

I blame John Seymour. Since reading his book ‘Self-sufficiency’ as a student lodging in a Devon cob farmhouse, I had been harbouring an ambition to live ‘the good life’. I wasn’t sure how I would get there, but that was my dream. Clare was more realistic – but she made good jam and the chickens were hers. We shared a belief in green values and we were looking for somewhere to put those green ideas into practice.

My record in house-buying is not particularly successful. The cottage I had bought a year or two before as my dream home turned out to need almost total renovation, as I discovered when moving the piano in, and my foot dropped through rotten floorboards. In retrospect this was a blessing in disguise as it enabled me to develop some basic building knowledge, without which ‘Hollow Ash’ would not have been possible.

It was when this cottage eventually sold that we had to make a decision; should we pay off the mortgage on the Stroud house, move upmarket in or around Stroud, or go for the big one – move somewhere with land and potential for our ‘dream house’?

The search

With money in the building society we thought we would see what was available; indulge our dreams; check out the possibilities.

So began a happy time of house-hunting. The postman delivered dozens of property details, most of which went straight in the recycling bin. We set off when we could, children bundled in the back of the car, to seek out the few which appeared to have possibilities.

We had sketched out our ideal; a modest cottage in need of renovation, set in say seven acres – enough for garden, orchard, pasture and woodland – in a quiet, secluded but not remote position, with a view. It became obvious very quickly that we could not afford anything suitable, or even half-suitable, within the proximity of Stroud, on the edge of the Cotswolds. We were working on a budget of £80,000 and the best we saw for that was a semi-detached, stone-built cottage right on the edge of the conurbation with extremely steep stairs to small bedrooms, a damp, cold kitchen and a moderate garden. We walked beautiful walks in the five valleys around Stroud, saw beautiful properties in nearly ideal settings, and pointed out to each other particular features of the vernacular or position, all the time becoming more and more despondent at the realisation that anything to which we were attracted was well out of our reach.

We spread our search wider. Nothing drew us south; Bristol would have its effect on any properties in that direction. To the east were the high Cotswolds and its villages preserved in aspic – nothing for us there. To the north were the flat lands of the Severn Valley. So we turned to the west, to the Forest of Dean and the River Wye, two beacons of nostalgia from my youth.

My mother had been evacuated to the tiny village of Whitebrook in the Wye gorge, and she first took me here at the age of eight. I was deeply impressed by the place and the way people lived within the landscape and did not dominate it. ‘Uncle Boy’ kept chickens and grew vegetables, and cut his own firewood. We toasted bread on the open fire in the small front room. My first attempt at joining in this good life was not portentous; thinking I might imitate Uncle Boy and chop some kindling I pulled rather than levered the hatchet from the chopping block and knocked myself on the forehead. I played in the brook, walked the tracks and lanes, climbed the hills and gathered armfuls of bluebells. As I said, compared to the flat urban landscape of Chichester it made an impression.

Ever since that holiday I think I have been trying to live life connected to the land. Somehow it seems much easier to do away from the crowded southeast. A geological field trip to the Forest of Dean confirmed to my teenage mind how life in the hills and valleys was more ‘real’ than among the estates and tarmac of Folkestone. In effect I have spent my adult life gradually getting back to this place, gradually moving west.

However, moving away from Stroud would make the change in our lives much more drastic; it would mean changing jobs, making new friends and finding new support networks. It all became more serious. The prices further west were lower, but not that much lower. We might have kept going into rural Wales or into Shropshire had we not found Hollow Ash. It did not match our ideal criteria; it was a barn with only one acre, but for the price (£40,000) it beat anything we had seen, and at 36 miles from Stroud it meant I could commute to work (just) until I could get another teaching post closer.

The Vision (Being green – in both senses)

Having found a potential plot we had to face reality. Were we what the small ads call ‘time-wasters’? Armchair dreamers with time and talk but no commitment? Or because we wanted to avoid this label were we in danger of taking on more than we were capable of, young, naïve and inexperienced as we were? There were certainly more warning voices than supporters among our friends – “It costs more than you think!” and “It can put a relationship under strain”. Family members remained diplomatically neutral (which probably meant they thought we were being unwise but didn’t want to dampen our enthusiasm). Most people could not see the vision we had and, although too polite to say so, thought we were mad.

What was our vision? A disused barn presented us with the opportunity to put into practice some of the green ideas and beliefs we had both paid lip-service to in the past. Within the stone walls we could build ecologically; using reclaimed materials where possible, incorporate solar water heating and a wood-burning stove, masses of insulation and a compost toilet. Outside we would have enough land to grow some of our fruit and vegetables, keep chickens for eggs, bees for honey and maybe even a house-cow. We would plant trees and dig a pond for wildlife. We would put up an owl-box to avoid feeling guilty about converting a barn. Our children could grow up healthy and happy, with their roots in the soil.

The alternative was to stay in Stroud within the network we knew and loved, to maintain and improve the end-of-terrace house, try to restore the fertility in the allotment and nurture our embryonic craft skills.

I think we rose to the challenge. I’m not sure we could have forgiven ourselves for not giving it a try. And once we had taken the first few tentative steps towards purchase, the project took on a momentum that would have been difficult to stop. In the end we had to push very hard to achieve ownership, so we certainly didn’t take it on by default. We were 100% committed. Naïve and inexperience maybe, but totally committed.

Negotiating

Having seen the barn in twilight and liked it, we spent the next week discussing its potential, trying out our ideas on each other and raising possible obstacles to test each other’s commitment and check the flights of excitement that tended to arise from time to time.

The following weekend we went to take a better look in daylight, and our dreams collapsed like a house of cards as we arrived to find several other vehicles there, and small clusters of people standing in and around the barn, looking, pointing and marking out imaginary walls of their own dream houses. We looked at the ‘trespassers’ and imagined their bank accounts big enough to buy outright, and their builder contacts. We were on a flight of fancy; people like us didn’t really do this sort of thing. We weren’t in the know and we didn’t stand a chance. We went home sobered and depressed.

However, we had met the farmer who was selling, and had made a point of introducing ourselves, expressing cautious interest, asking lots of questions and taking the telephone number. We are great believers in using a personal, direct route where possible, and feel this has helped us in several of our dealings in this project. We learnt that the barn had been on the market for five years, originally, at the height of Nigel Lawson’s housing boom, for double the present asking price, but it had not sold. It was too small for current agricultural needs and money from the sale would fund the building of the farmer’s retirement bungalow. It was being sold with Full Planning Consent, which would have become void had the owners not laid a token pad of concrete to show work had started.

Despite the realisation that we could be in competition with others, over the next month we visited the barn as often as possible, and at home began to organise ourselves. We got books from the library, from the Centre for Alternative Technology, and we gradually formulated a plan of what we needed to do to move forward:-

- Sort finance

- Get professional advice on the structure

- Get plans drawn and passed

- Put in an offer

In retrospect, putting in an offer so late was risky – we could have lost the sale – but we were so cautious; we tried not to let the hearts rule the head. But we did have the advantage of preparing ourselves over the winter when the housing market tends to hibernate. Also, as luck would have it, we learnt through the farmer that before long we were the only contenders left. Our fears about those other prospective buyers proved unfounded. What it was that put them off was uncertain; perhaps the size was too small (under 1000 square feet with no obvious way of putting in a second floor); perhaps sharing access with farm vehicles was off-putting (the track runs right in front of the barn); or maybe the lack of services presented too great an obstacle. Whatever the reason, after the initial flurry of interest following that grey, grainy advertisement, we were left without immediate competition to investigate the necessary elements of our plan.

Finance

How much does it cost to convert a barn? This is not an easy question to answer, but ‘more than you think’ may be a fairly reasonable response. I worked out a rebuilding programme, as I saw it, from underpinning up to a new roof, and sent it out to three recommended builders. We got a shock when the tenders came in; all were beyond our means and it became clear that I would have to do a lot of the work myself. Builder friends were understandably reluctant to put a figure on the overall cost of materials, but the helpful officers at Building Control gave a tentative figure of £40,000. To be more accurate I used the detailed building programme I had drawn up, to try to estimate quantities of materials, and from there, costs. In hindsight, despite adding 10% to estimated costs I underestimated seriously.

Still, having got a figure which was within our budget we looked for someone to lend it to us.

Although I believe the situation has changed now, in 1993 almost no building society was interested in lending on a derelict property. Our first inquiry was obviously to the Ecology Building Society and we were most disappointed to learn that they had no funds to lend at that time. However our local building society invited us to an interview, and having worked out our income and estimated our needs we presented our case to a young manager and in due course heard that they would release money in stages (stage payments) subject to regular inspections by a surveyor, for which we would pay. As the negotiations dragged on into the spring we contacted the Ecology again and were delighted that they now not only had funds available but that they would be interested in lending on the property. The more we dealt with the Ecology, the more impressed we became; they gave us good advice, they were efficient, they didn’t require stage payments nor did they require surveyors’ reports. They set a deadline for completion and insisted on a certain level of insulation (which we were more than happy to meet) and asked for photographs to demonstrate progress. All this suggested a very different approach to building finance; over the years we felt the Society took a personal and ecological interest in our project, as well as a financial one. We were off to a good start.

The Structural Survey

To our unprofessional eyes the barn looked in fairly good condition; the tin roof put on about 30 years before had kept most of the water out and most of the walls looked sound. The main problems appeared to be:

- •a large crack between a side wall and a gable end

- •a large old ash tree about six yards from the barn

- •one or two joints in the trusses looked suspicious – one definitely damp

- •no damp-proof course

- •lime mortar eroded by wind and weather on the corners

Such was our desire to do things right that we paid for a full structural report, which turned out to be mostly unintelligible technical data. What it basically recommended was underpinning all the walls and dismantling and rebuilding the joints of all the trusses. The architect was reassured to receive the report, but we were £1000 poorer and not noticeably closer to our goal.

The Architect

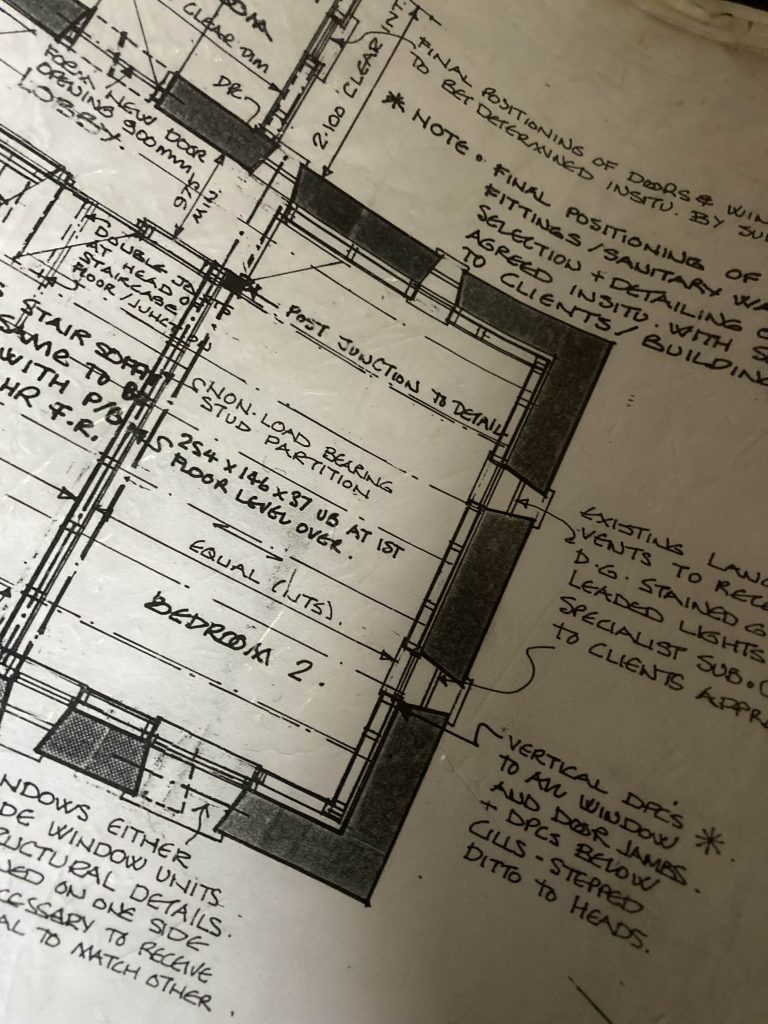

Clare’s cousin is an architect and he was a great source of expert advice in the early days when we were learning the procedures. Peter helped us sort out ideas for the floor plan, suggested questions for the planning authority, and using measurements and photographs we supplied he prepared – from the other side of the country – a full set of drawings to satisfy Building Control.

Building Control

We approached Building Control from a position of ignorance. We made an appointment and took our list of questions to the local council offices in Ross. Building Control seemed to be set apart from the more mundane council business; we asked at the social security counter and were directed through a door which led upstairs. At the very top was a door marked Building Control. On entering we met two officers settled comfortably behind their respective desks which were piled high with papers. Near the door was an aged computer and in a basket under the window was a jack russell terrier. We immediately felt these were people we could talk to. Mr. M, the senior officer was knowledgeable and decisive and wrote in a meticulously neat hand. Mr. H. had a keen interest in alternative sewerage systems and, we found out later, drove a red sports car. We felt we could trust what these people told us. The difference between planners and building control, they told us, was that planners told you what you could build and building control made sure it would stay standing. They thought most barns cost about £40,000 to convert, which shocked us, but they allayed our worries on the various questions we had relating to the ecological aspects of our building plans. South Herefordshire, it turned out, was quite liberal in its attitude to innovative and experimental building ideas. We came away from our first meeting optimistic and with detailed instructions for undertaking a percolation test.

When Peter had drawn up the plans and we took them in with our fee, they gave us a set of cards to return one at a time at certain stages of the build. This became impractical as the build was unconventional both in time-scale and method. So one officer or another came to visit around every six months, or by appointment to discuss a particular detail, like the compost toilet. We always found them most helpful; regarding the toilet we were told, “Let’s see how it goes.”

The Planner

We took our early ideas to the planning office and, as with Building Control, from a position of genuine ignorance we asked his advice on what would be possible. While we didn’t see the logic behind all the restrictions we nodded and noted them down. Basically openings could only be made in the masonry where an opening already existed. This meant a large wood-panelled section facing the southwest could be replaced with a large picture window as could the original gable end doorway. However, he also agreed to the widening of two ventilation slits which would let light into the children’s bedrooms, and he also allowed the use of ‘Velux’ roof-lights to enable a potential first floor to be lit. Even better he pointed out that we could put on an extension at the rear. ‘Our’ small, dark barn took on the potential of a more spacious, light-filled home.

Some restrictions suited us (no conservatory, a hedge of native trees) and some allowances surprised us (solar panels on the roof). The only restriction which caused us concern was the roof covering. We would have liked to keep a corrugated iron roof (or similar – some new industrial sheetings are coloured) but that was out of the question. It had to be ‘slate, or slate-like material’. ‘Slate-like’ meant artificial slate which to our eyes looked too flat, dark and shiny, and went against our principle of using low-processed materials where possible. We investigated slate and found a warehouse full of reclaimed welsh slates in Caerphilly; the roofs of the terraced houses there were gradually being replaced by concrete tiles. But they were so dear we really couldn’t afford them. The local vernacular – apart from tin – was clay pantiles; 35p each as against £1.25 per slate. We prepared photographic evidence and plucked up courage for our first argument with the planner. Clare ‘phoned for an appointment.

“May I ask what it’s about?”

“Well, it’s about the roof covering.” And she found herself outlining our case over the telephone.

“Yes, that’s alright. I’ll write a note of consent.”

And that was that. People tell such horror stories of planners, but ours was great, a ‘Sweetie’ as Clare describes him. I think a lot depends on how you approach them.

The Estate Agent

I always thought that estate agents would be keen to sell a property. Especially to cash buyers. But we experienced a most unusual inertia – even antagonism – from the agent charged with selling the barn. We found requests for information ignored and finally talked directly with the farmer to keep lines of communication open. We had completed our preliminary investigations (survey, planning, building control, plans and costs) and were ready to proceed just before Christmas 1993. Having been quite cautious and thorough before the decision, now it was made our (my) impatient character wanted to get things moving before the Christmas break. But one delay after another meant that we didn’t exchange until April. How we didn’t lose the sale to someone else I don’t know.

The most serious problem was over the area of the land. The advertisement had specified ‘1 acre’. Not ‘Approaching 1 acre’ or ‘Approximately 1 acre’. For a family which had tried to grow vegetables with full rotation on two 10’x 6’ beds; and had celebrated a toddler’s birthday picnic tea party complete with paddling pool for half a dozen friends and attendant parents on a two-level lawn 20’ x 10’; and for me who had spent all my adult life wanting land; land was very precious and I wanted an acre – nothing less. I borrowed a 30m tape measure and spent many hours (thanks to Chris M. who held the other end in the bitter east wind and snow) measuring between fixed points and drew up a map using trigonometry and found that what was on offer was at least one tenth of an acre short. We met the farmer, his son and the agent on site to ‘discuss’ the matter, but it was only when I quoted our solicitor and pointed out that ‘some people build a house on a tenth of an acre’ that they worked out where the boundaries could be extended.

The experience did not enhance my opinion of estate agents.

The Solicitor

Apart from going on holiday at a critical time in the negotiations, we have nothing but admiration for our solicitor. She was efficient, personable and full of good advice. We can’t really blame her for her choice of holiday date, but it resulted in us nearly losing the sale. She put the file in the hands of her supervisor for the duration.

We received a telephone call from the farmer:

“Mr. Harris, I am not a happy man…”

He had contacted his solicitor for a progress report and received the news that we had no mortgage arranged and were therefore not serious about the deal. The fact was that we did not need a mortgage to buy the property – we only needed it for the conversion. But our solicitor’s boss hadn’t thought to check with us before divulging our apparent lack of financial arrangements. If the farmer had not been forthright enough to ‘phone us we could have lost the sale. We didn’t receive an apology.

It’s ours!

Eventually all the hurdles were overcome and we could see the way clear to the finish line. Spring was rapidly transforming the countryside and we were impatient to own our little bit of it. In the small town house we felt claustrophobic.

The farmer was most cooperative. He allowed us to get our caravan delivered on to the land a week or two before completion. We worked out a deal whereby we bought the fencing materials and he put them in.

On April 24th, 1994 Clare and I visited our solicitor’s office. During the brief wait before our appointment we paused and reviewed the hectic and exciting previous six months. After all the ups and downs, hopes and fears, we were at the threshold of making our dream a reality. In the office, after just the slightest sensation of cold feet – the nervousness which comes at a turning point in life – I signed the appropriate boxes and we took possession of our corner of the Earth, potentially our home but at present a very expensive picnic site.

Caravan

At this point we had two homes: the house in Stroud which came to be used more and more as a hotel, and the caravan at Cwm Madoc, which occupied our creative and organisational energies. The caravan was bought from near Kidderminster for £350, including delivery. It is a 28’ Viking, dating from the 1960s, complete with original gas stove and gas lamps. It impressed the chap who came to connect us to bottled gas and check the system. We replaced the gas fire with a small wood-burning stove bought through the small ads, found ourselves a chemical toilet (again through the small ads) and used a jerry can to collect water from the farm. We had the basics to survive.

From those simple beginnings began the long, slow haul to create a home with all the complexities – unbelievable complexities – demanded by modern, western life.

Water

The priorities were to get water, electricity and a ‘phone line laid on and to build a workshed in which to store furniture. It was with the water connection, our first major earth-moving operation, that we made our first major error. Knowing nobody in the locality, except the farmer, we asked him to recommend a contractor to excavate a trench and lay the pipe from the road down the farm track to the workshop and caravan. The mistake was (I hate to admit it) not getting more than one quote. No, it was worse – we didn’t even get one quote. We didn’t even ask for an estimate! The contractor we asked must have seen us coming and we ended up paying well over the odds, plus VAT.

The whole episode brings back bad memories; while the JCB was tearing our precious ground to pieces in the rain (stressful enough) Clare was lying ill in the caravan unable to stand without feeling dizzy. So she was no help at all when it came to directing operations, checking positions and depth, organising fittings and connections. The trench was halfway to being back-filled when Colin, the farmer’s son reminded me that the ‘phoneline was supposed to have shared the same trench. I had to ask the contractor to re-excavate the trench, slightly less deep, put in the ‘phone cable and backfill again. Perhaps it is not so surprising that the final bill was high.

Telephone

The connection of our telephone line into the BT network is a small saga in itself, which I will skip over except to say that, by the time we finally heard that reassuring dialling tone, we had stacked up enough compensation to pay for the first 1½ bills. Then when our water was being connected a passing van, while avoiding the stationary water company vehicle, drove off the tarmac into the soft verge, leaning so much that it hit and split in two the telegraph pole which held our precious connection. Life never seemed dull.

One ambition was realised in that I had a three-digit telephone number – Skenfrith 465 – at least for a few months until the exchange was upgraded and we were given the ubiquitous six digits.

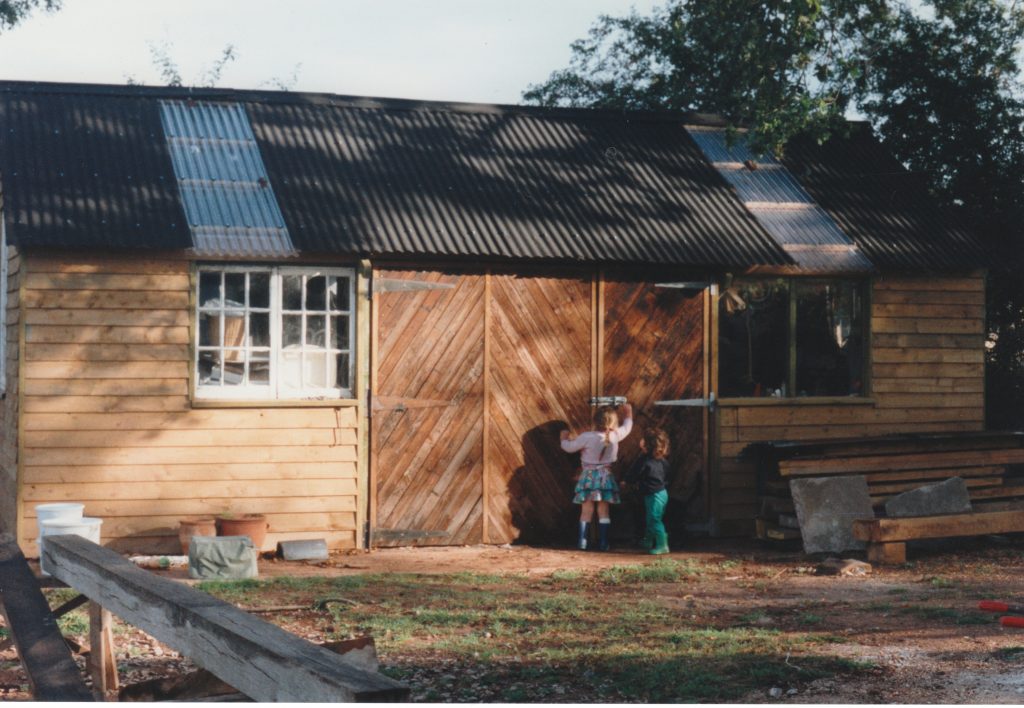

Workshop

Building the workshop was more fun and much less stressful because I was doing it all myself. The concrete slab was laid over a DPM and ‘jablite’ (expanded polystyrene) insulation to form a base 14’ x 24’. Our good neighbour, Phil, full of advice, spent several hours helping me and showing me how to ‘polish’ the surface to a smooth finish. The walls are block up to window level and studwork above with a facing of weather-boarding. The roof is reclaimed corrugated iron and the windows are an assortment of frames salvaged from skips. In retrospect there are many elements of the design which I would not repeat, but it has stood up to the weather reasonably well. The worrying mistake I made with this project was to not inform building control before the slab was laid; I had to dig down afterwards to show the officer how thick it was. The workshop became home to a washing machine, and later we used it to store our furniture.

Electricity

Once the workshop was up we had somewhere to connect an electric cable. This time we took Phil’s recommendation and asked a local builder to excavate the necessary trench down the fence-line of our ‘orchard’ and across two of Colin’s fields to share the transformer for the farm. This was cheaper than going to the nearest pole and and paying a proportion of a new transformer. Once the trench was dug, and we were waiting for the MEB to lay the cable, it rained heavily of course. The sides of the trench were steep and slippery and one of Colin’s ewes fell in, ending up on its back. By the time I found her she was the same colour as the soil, wedged fast and in a bad way. Colin managed to get her out but she died a few days later. Colin was very good about it but I felt rotten; we had come here to live alongside the natural and the farming world, and it was upsetting how easily things could go wrong.

When the MEB crew eventually arrived the first thing they did was to make a pot of tea. To do this they started up a generator to boil an electric kettle. Watching them lay the massive armoured cable, by hand, over ¼ mile, was impressive, and it was a great relief to get the trench backfilled and the cable connected.

With electricity connected to the workshop we could string an extension lead across to the caravan for lights and a fridge. In a way it was a shame to no longer use the gas lamps with their soft yellow glow and gentle hissing, but with two young children electric lamps were safer. More usefully we could connect up and use a washing machine in the workshop. Up until then we had used the launderettes, both the one in Ross and the one at Clare’s Mum’s. Colin had let me run a lead from the nearest farm building when I needed to use a drill, but now I could use electric tools in the workshop.

At a later stage I buried armoured cabling from the workshop to both the caravan and the barn, each having their own consumer unit.

Burning the bridge

Our house in Stroud was on the market as soon as we had bought the barn in April 1994, but it wasn’t until December that it sold. That first summer was an exciting, nervous and slightly unreal time, like one long series of picnics with a stream of visitors who came to see what we had done. Some were intrigued, some envious and others disbelieving at what we had taken on. Those who said little or nothing probably thought we were mad.

“What are you going to do with all this land?” One and a half acres, remember.

Our life became a routine of Tuesday to Friday in Stroud, so that I could get to work easily, and from Saturday to Tuesday morning we escaped to our ‘dacha’, usually with a trailer-load of clutter to go under the caravan or into the half-completed workshop. We gradually filled the caravan with clothing, bedding, curtains, kitchen utensils, decorations, books and toys. The biggest problem was looking after the chickens. The best solution was for them to commute with us, so each time we travelled to and from Stroud the three hens would be put in a cardboard box between the two children. They loved it in the long grass of Hollow Ash and were often reluctant to be caught; some Tuesdays we would spend half an hour chasing the Light Sussex (such a nervous breed), risking being late for my afternoon teaching session. We never left her here alone – but she came close to it.

When the Stroud house did sell, a week or two before Christmas, things moved up a gear. We hired a van and moved out in two trips to Hollow Ash and two to Clare’s Mum in Woodchester. We stocked her garage half full and loaded her attic with boxes. Don’t tell her but some of those boxes are still there, after 28 years! Never again! It is exhausting work. I unloaded single-handed into an unfinished workshop – there were no doors but at least the roof was watertight.

Christmas was spent in the caravan, with a small fir tree in a pot on the sideboard. After Christmas the weather turned cold and Clare took the children to her mother’s in Stroud, leaving me to work on the workshop. However, I was enveloped in freezing fog. Even sawing and hammering was not enough to warm me. I didn’t see the sun for five days; it was a massive dampener of my spirits. But when the fog did clear I was rewarded with the most magnificent hoar frost I have ever seen. This truly is a beautiful place.

When Clare and the children returned we contacted a local recommended builder to discuss the project and ask when he could start. January, he said.

Builders move in

We employed a couple of jobbing builders, recommended by our good neighbour. They convinced us that they were up to the job, so we took them on to be paid at an hourly rate, to be reviewed stage by stage.

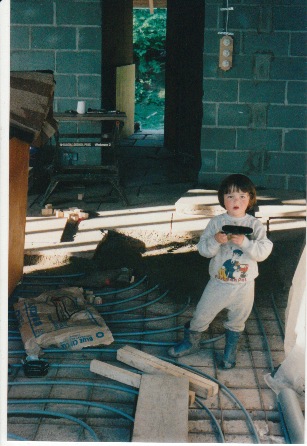

A few days into January 1995 a JCB had transformed our unspoilt, neglected plot into a mud-bath. Part of the back wall was demolished and the roof held up with acro props. Not long afterwards, however, the walls had been underpinned with concrete, the corner with the worrying crack had been rebuilt with the stones tied in to each other. Soon the extension foundations had been laid, the floor levelled and the concrete slab laid. Gradually block walls went up inside the stone shell and the extension walls were raised.

While it was exciting to see progress on the barn, this period was mentally draining. Decisions needed to be made quickly, some of which we found very difficult. For example, what size should the toilet chamber be? Should we take advantage of the unexpected extra space and create a cellar? Should we take away the earth banked up against the east wall, cutting through the old ash tree roots? Was it worth putting in an external DPC in the stonework? For the record, the chamber was about 10’ x 5’ x 4’ tall, which as it turned out was very spacious (one decision well made). The cellar would have cost over £1000 – unbudgeted. We got cold feet and filled the space with subsoil. We later ran out of money, but we have also run out of storage space (one opportunity missed). We reduced the ground level around the east end to prevent damp penetrating, but the ash tree died (one huge disappointment – perhaps inevitable). Through lack of a persuasive argument one way or another we did not put in a DPC, thus saving £500. It would have been a chemical injection into a thick stone and rubble wall – I can’t imagine it working. So far we have seen no penetrating damp, except around the door. (So far, so good.)

The builders wanted to press on with the job and would sometimes make decisions without me. For example they were about to put in stone lintels when I learnt from building control that wooden ones are fine. They were reluctant to fill the cavity with 2” fibregass insulation batts. One day they had a doorframe for the backdoor delivered from the builders’ merchants. I had to send it back because it had an iroko threshold. Whilst they had much more experience than me I found as the project progressed we had different expectations. The only mortar they used seemed to be 1:3 cement to sharp sand – very hard, very grey, and to my understanding not suitable for an ancient stone building. Alarm bells rang when they let slip that a house ‘ought to look like a house’ while we were intent to preserve the appearance of a barn.

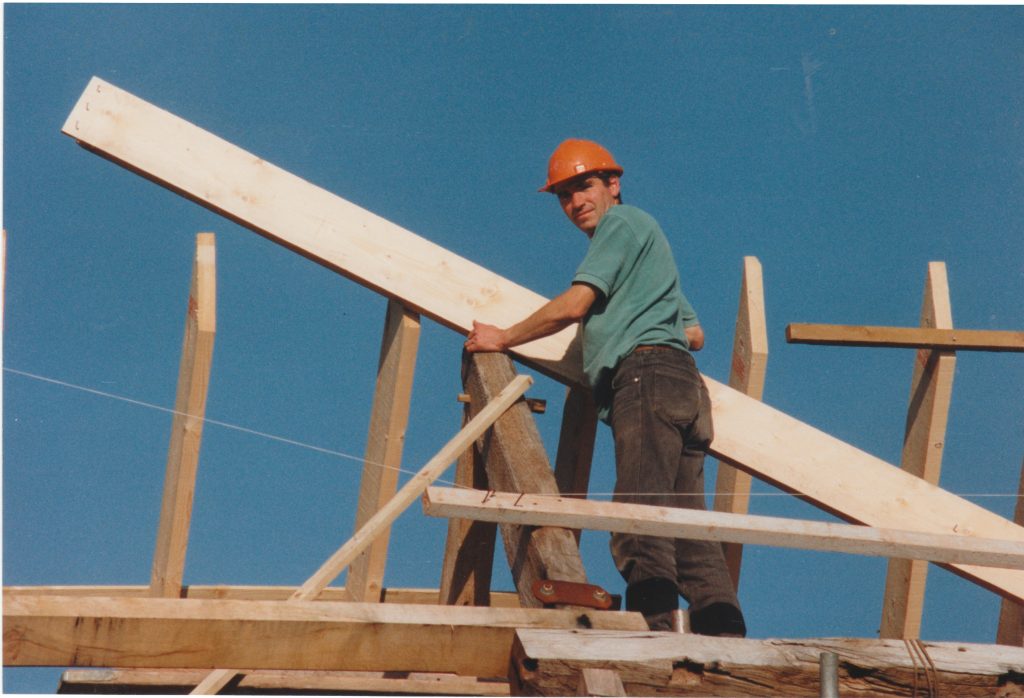

It was when the roof eventually came off in the summer and they were using a chainsaw to repair the rotted joints in the trusses, and they were using many hours (time = money) to think how to rebuild the roof – and our monies had dropped to an alarmingly low level – at that point I decided I would have to take over the building work myself.

Although to look at our home it was more of a wreck than ever, it was with a huge sense of optimism that I reclaimed control of the project.

Going it alone (True ‘self-build’)

At the point when we took over we had a solid shell with most of the original walls standing, repaired where necessary and with new nib walls and window openings. Inside was a concrete floor slab with internal walls completed including window reveals and first-floor joists. The roof trusses had been strengthened where necessary. The extension at the rear had most of its blocks laid. From the outside the barn looked a wreck; but our money had been spent on the heavy preparation for the more constructive phase. Clare later admitted this was the low point in her morale although she said nothing at the time.

There followed a lot of thinking time and measuring and drawing to work out how to fit a new roof, much thicker than the original, onto walls which were neither square nor level. I prepared some new fairly complex roof timbers and purlins in oak, and raised them in the rain with the help of a neighbour from the village. This was the way of working now – working alone on most jobs, using Clare when extra muscle was needed, and calling in friends when the task was really heavy. The successes (like the mortice and tenon joints in the roof timbers fitting) and the visual progress as the skeleton of yellow rafters extended gradually across the barn, fuelled my enthusiasm. Between August and December 1995 during a beautiful autumn the roof was constructed and felted, ready for tiling. This involved finishing the walls in the extension and building up the stone walls between the rafters. From January to July 1996 I tiled the roof and incorporated the two flue pipes and the solar absorbers. At last most of the weather was kept out.

Once the 44 window- and door-frames were in place (again, thanks to friends) we were ready for glass and with the wind excluded we began to sense real progress. In January 1997 we invited staff from my old school in Stroud (having obtained a post at Gorsley in 1995) and we shared a meal in the barn. An 8’ x 4’ plywood sheet covered the back entrance to try to keep out the winter chill as we still had no back door, and we lit a blazing fire in the wood-burning stove. Two years after building work had started we had succeeded in warming the barn: our unofficial house-warming party.

The project

A breakdown of who did what:

Builders

- Underpinning

- Masonry repairs and build

- Excavation around site

- Floor

- Blockwork and wall insulation

- Roof removal

- Truss repair and support

Self-build

- Extension walls

- Roof

- Extension window frames

- Back door

- Electrics

- 2nd fix plumbing

- Flagstone and oak floors

- Window furniture

- Solar absorbers

- Chimney flues

- Window cills

- Window boards and window seat

- Pointing

- Basins, baths and sinks

- Toilets

- Shower tray and tiling

- Wood panelling

- Varnishing and painting

- Drainage pipes

- Internal joinery including doors

- Underfloor heating

Experts

- Most window joinery

- 1st fix plumbing

- Plastering

- Compost toilet chamber

- Rainwater harvesting system

- Guttering

- Staircase

- Roof insulation

Friends

Grateful thanks to the following:

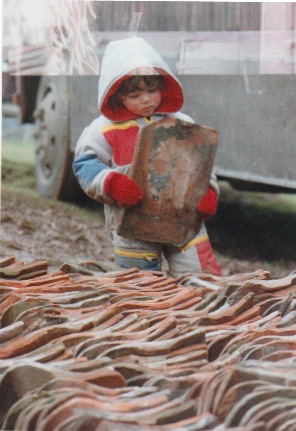

- Mark for helping to collect and unload recycled barracks for timber.

- Frank for helping to lift oak roof timbers into place.

- Sue and James for helping to move Rayburn and large window frame into place.

- Dave and Roger for loading, unloading and laying huge quantities of flagstones.

- Chris M for holding the end of a tape in the snow and screeding the toilet chamber.

- Nick for endless advice, and specific help with laying underfloor heating pipes and extending the flue.

- Paul M for helping to dismantle the roof.

- Chris & Liz F for constant support and cakes and practical help.

Trials and tribulations

There is no doubt I gained immense satisfaction from doing a lot of the work myself. The pleasure derived from being in control, knowing what I was about and seeing the progress before my eyes. However 1997 was marked by great anxiety too, resulting either from not knowing quite what to do or how to do it, or, having called in experts being disappointed with the results in some way. Here are a few cautionary tales:

The guttering was left to a recommended installer, but I will have to redo one section which slopes the wrong way. Moral: Check the work while the worker is still on site.

Worse was the glazing. In order to save £100 we persuaded the glaziers to fit the units they had made rather than employ a local fitter, and they assured us the units would not need silicone. When the rain came – horizontally, as it does here – it came around the glass and onto the window board in puddles, and the beading absorbed the water and buckled. They were very good and came back to re-fix it all with silicone. Moral: Choose workers who are experts at their job.

I had put off making a staircase because I did not feel confident, so when I eventually asked our local joiner to build one the top floor and oak posts were already in place and the wall was plastered. He got very frustrated trying to find a way to build it in situ but succeeded in the end. Moral: Don’t put off difficult jobs.

The joiner in Hereford we asked to make our windows gave us a very good price. However he didn’t follow our instructions well. We have outward-opening french doors and the wrong one opens first – always at risk of being caught by the prevailing wind. He also assured us that we could have inward-opening windows at the front, in the french style. However, they don’t have the french detail and they invariably leak when rained on so I have had to fit shutters which we must remember to close in poor weather. When we asked the joiner to make four more windows for the extension he delayed for so long that I went and collected the timber from his workshop, bought a router with the money saved, and made them myself. Moral: Don’t take what someone says on trust; ask to see the drawings and check they will work.

‘Warmcell’ insulation was pumped in between the rafters by contractors, who in the process sat on the watertank and buckled the lid. Consequently a quantity of the insulation (recycled newspaper) entered the water system giving us the dubious pleasure of reading snippets of old news, delivered through the tap, while taking a bath. One can only fear that the same attitude has resulted in us having voids in the roof where there should be insulation. Moral: Watch contractors closely. Unfortunately I was working away from home on the day they came.

For one of the many loads of scalpings we ordered we thought we would try a different haulier, as we found the regular chap full of gossip. You would see his eyes taking in everything, probably to fuel gossip at his next call. We had ordered ‘3” to dust’ but it turned out to have rocks up to 6” in it – almost suitable for building with, but not for laying a hardstanding. Moral:Check what the lorry contains before it tips 11 tonnes of unsuitable material in your drive.

The time when I came closest to despair was when, having laid half the flagstone floor on the previous day, I found most of the flagstones wobbling. I could not understand the process that caused this, but after some thought concluded that the only possible explanation was that the flagstones flexed through differential expansion due to the moisture in the bedding layer. Moral: Be prepared for anything, even taking apart and re-doing a heavy day’s work.

Other mistakes due to my inexperience, incompetence or impatience include:• not completing the sanding of the bedroom floors before moving in, with the result that we lived with unsightly and splintery floors for four years;

• screeding the bathroom floor too high due to indecision about using tiles or flagstones, resulting in hours of work chipping at it with bolster and hammer to lower it;

• and (most embarrassing) standing back to admire a complicated piece of oak beam and post joinery, then realising I had built it through the scaffold tower. Luckily the work was pegged so I could dismantle it rather than hacksaw through the scaffolding.

I don’t want to give the impression that all so-called experts are more trouble than they are worth, although that is certainly how I felt a lot of the time. We found a great JCB driver, a superb plasterer and a brilliant duo to design and supervise the rainwater harvesting and sewerage systems. All these were thinking builders who made suggestions and were reliable. Without them I would have floundered.

Moving in

I knew that once we moved into the barn it would be very difficult to continue interior work so I put the day off as long as possible. We were under pressure, however, from the building society, who understandably would feel more secure when the project was completed; we were a few months past the 18 month ‘deadline’. There was also the oncoming winter which threatened another difficult period in the caravan, with children growing bigger, and their oft-repeated question, ‘Will the barn ever be finished’.

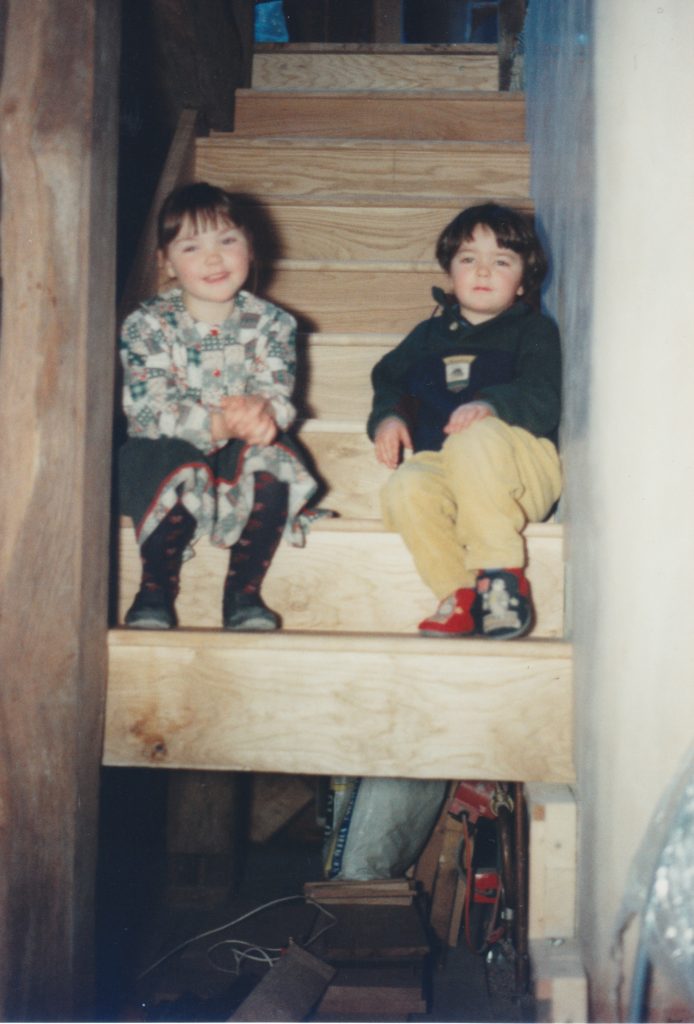

So in October 1997 we packed the children off to their grandmother for a few days’ holiday and Clare and I worked solidly to prepare two bedrooms ready for beds, and made the rest of the house as comfortable as possible. When the children returned they found the building site transformed into a home. They now shared a room that was bigger than the whole caravan. They were so excited at all this extra space that they spent the evening running up and down the corridor between their bedroom and the living room.

At this stage there was a table and chairs in the kitchen, and crockery in a temporary unit. We had a Rayburn, a sink in the back kitchen and a working and decorated bathroom. However the only lighting came from extension leads from the only connected socket. There were no doors, no stairs, no floor in the living room and the shower room was full of building clutter. There was no washing machine and the food was cooked in the caravan and brought over to eat.

That first winter felt strangely insecure, rather like camping in a barn. We were battered by severe gales over the New Year; there was nothing between us and the Welsh hills except large double-glazed units, and the wind hit them with extreme force, and rattled the tiles. It was through surviving trials like that that our confidence in the building grew.

We didn’t realise until later that we needed a ‘Certificate of Occupation’ from building control, before moving in. The house was better sorted when they eventually came to check it; the stairs had bannisters and there were no loose cables, and they were satisfied.

There is no doubt that it is harder to keep going at the same pace once the comfy chairs have been put in. You get to live with the unfinished details and even fail to see them after a while. Other things begin to take priority, like children, gardening and, well, living. But we pressed on towards that elusive goal ‘completion’. The shower room was emptied, tiled and grouted, the oak boards dried, planed and laid, doors constructed and hung.

Building control gave us the all-clear early in 1998 and it was a pleasant task to inform the Ecology Building Society, and thus obtain a ½% reduction in mortgage interest. There followed a frantic three months to organise, check and collate our VAT claim. The cheque was for £5000 and its arrival marked a milestone: the end of being answerable to all the various authorities. We were like other families now, and could pay our council tax at the full rate. As we feared, we were put on band E.

Out of interest, and to ensure we were adequately insured, we had the property valued. In spring 1998 it was worth about £170,000. Purely from a financial perspective, it had been worth it.

The details

Insulation

Insulation is cheap and we put in what we considered was plenty, but it looks meagre compared to today’s energy-efficient houses.

- • Under the concrete slab: 2” expanded polystyrene (it should have been 4” minimum)

- • Roof: 8” recycled cellulose (‘Warmcell’) within the rafter space.

- • Walls: 4” insulation block and 2” fibreglass in the cavity.

- • Windows: double-glazed with silicone barrier between the glass. ‘Pilkington K’ in large units.

Potential cold bridges occur at the window reveals because the windows are set within the stone walls to give large inner window boards. We used ½” polyurethane foam board to line the walls at these points, but it does not give a particularly strong wall surface.

How well does it work? The temperature of the house rarely drops below 60°F (15°C) and most of the time it is noticeably warmer than outside. On summer days it is pleasantly cool. It is always an acceptable temperature for getting up in the morning. What I didn’t get right was the draughtproofing; there are small gaps where the roof timbers cut into the wall, and around the windows and doors. This is not helped by the fact that the pointing has never been finished.

Passive solar gain

We are fortunate that our barn faces between south and southwest and benefits from solar gain, particularly in the afternoon. The glass on the south-facing windows is selectively coated (Pilkington K) to increase the solar gain within the building. We deliberately chose solid wall construction and thick concrete floors with flagstones covering about half the floor area in order to store heat gained and to limit fluctuations in temperature.

How well does it work? It is particularly noticeable, and welcome, coming in on a winter’s evening after the sun has been shining, how warm the barn is. The strong summer sun is blocked from the living room by a large overhang on the eaves. On the gable end, where we have a huge expanse of glass, we could benefit from some shading, either muslin curtains, shutters or a pergola with grape vine or similar, as it can get too hot in the direct sun.

Burning fuel

When the house needs extra heat we light the wood-burning Rayburn, and when the weather is particularly miserable or we have guests round we light the wood-burning stove too. This stove simply radiates heat and is good to sit around in the evening, but the Rayburn also heats our water and cooks the food. When the hot-water tank temperature is up to about 60°C a thermostatically-controlled switch turns on the the underfloor heating pump. Warm water is pumped through 15mm Hep2O pipe tied to reinforcing mesh with potato-sack ties and set in a screed above the concrete slab. This made a very thick (11”) concrete/screed slab to act as a massive heat sink and store. The downside of this is that it takes a while (a day or two) to gain the benefit of heat from the floor, while the slab heats up, so it works best when the house is occupied constantly and the Rayburn runs all day, each day. Most consultants recommend putting insulation directly under the pipes to give a quicker response. 2” of insulation under and around the floor is not enough, and I daresay we lose a lot of energy into the ground.

We have six circuits in the underfloor heating but generally only run three: the shower + bathroom and the two downstairs bedrooms. This is because we don’t generally stoke the fire up enough to satisfy the whole system and also the small Rayburn is rather underpowered so we put the heat where it is most needed.

The fuel is wood, which is bought as offcuts from a local sawmill in 8’ lengths, cut, chopped and stacked by us. This is a time-consuming set of operations, even with a chainsaw. The wood spends a year drying in an open-sided shed; burning green wood is a waste of time and effort. Eventually we hope to buy a 2-acre woodland and coppice it for firewood.

Feeding the family

Since reading ‘Self-sufficiency’ 25 years ago, growing my own food, or some of it, has always been an ambition. In ecological terms food produced on your own plot is A Good Thing, saving food miles and having health benefits in terms of freshness and quality. The food is produced with minimal chemical intervention using the organic principals of the HDRA. I read somewhere that vegetable growing is the most productive use of land; that must be because it absorbs so much labour.

The vegetable beds are positioned on the old trackway – we brought in several trailerloads of topsoil to improve the fertility – arranged as 4’ wide raised beds separated by 2’ trodden earth paths. The total area of cultivated ground is about 600 square feet. I find this is enough to grow a basic variety of vegetables but not enough to keep us in potatoes, onions and carrots all year round. The 12’ x 8’ greenhouse and 20’ polytunnel provide cucumbers, tomatoes and lettuce and with practice could probably be more productive.

The fruit cage is 15 x 30’. Each summer we were overwhelmed by red- and blackcurrants, and we made enough cordial to last through the year.

We planted a small orchard when we arrived with old and local varieties of apple, with a few pear, plum and cherry. We are starting to get, after 7 years, serious quantities of fruit, enough for juice and possibly cider. This has meant building a mouse-proof storeroom to keep apples and other vegetables for the winter.

Chickens have been a good source of protein, both egg and meat. The only real problem has been the number of broody hens which manage to hide their clutches from us, resulting in too many chickens.

The sheep are excellent lawnmowers, and for several years we lambed for increase and for meat. This is quite time-consuming and a great commitment, so at present we keep just the four sheep. They are Ryelands, an old Herefordshire breed, and find them very suitable for our needs; they are small, hardy, friendly and do not constantly try to escape, unlike Jacobs, which we tried at first.

I used to keep bees until Clare became allergic to the stings and varroa wiped out colonies not chemically protected.

In the summer, cooking is done on a propane-fuelled gas stove, while in winter generally the Rayburn is used.

Water is collected from the roof and stored in a 16 m3 underground tank, from where it is pumped into the house through a string filter and an ultraviolet lamp before being held in the usual loft storage tank. Drinking water passes through the filter and lamp and additionally through an activated carbon filter. This was done to reduce our use of mains water but another benefit is that water without chlorine tastes better.

Water use

Water for the house is harvested from the roof, approximately 100 m2 in plan area. Multiplied by the average annual rainfall of 700 mm gives a potential collection of 70 m3. Using water carefully, for washing, bathing, showering, and flushing our one low capacity WC, as well as cooking, drinking, animal watering and polytunnel and greenhouse irrigation we use on average about 1 m3 per week. This is about ¼ of what the average family of four uses. The saving comes largely from having a compost toilet, needing no flushing.

The rainwater is collected in galvanised steel gutters and downpipes, channelled through underground clay pipes into an underground tank 4.8 x 2.4 x 2.4 m, which holds approximately 16 m3 water. The tank is positioned at the front of the barn. It was dug using a JCB, the concrete floor laid then the walls were constructed of poured concrete held in by plywood shuttering. The walls incorporated 4” pipes for incoming water and overflow, and small diameter pipes for electric cables to the float switches and for the outgoing water. Once the walls had set, the roof was cast in reinforced concrete on a shallow arch of plywood, with a 2’ square hole left for an inspection cover. The size of the tank had been determined to store enough water to supply the house during all but exceptionally prolonged dry periods.

Filtration

We tried using a fine mesh ‘sock’ fitted over the incoming water pipe to act as a filter, but found that it restricted the flow too much during spells of heavy rainfall, which are the best occasions for topping up the tank. As a result the water backed up in the pipes and overflowed (as designed) into the pond. We had very coarse mesh filters over the top of the downpipes, but these block quickly with leaves or algae, which results in the gutters overflowing in heavy rain. So at present we have no filters into the underground tank but clean the gutters regularly.

The pipe carrying water out is ½” diameter food grade plastic, and is fitted with a fine mesh ‘sock’ holding a float (so water is taken from the top) and a non-return valve (so the pump does not suck air). It is connected to a ‘Sure-flo’ caravan-type pump located in a protective and insulated container under an inspection chamber just beside the tank. It is too noisy to position indoors; all we can hear is a quiet hum when it is running. From the pump the water enters the house through a standard 25 mm blue alkethene pipe, past a stopcock to an area under the sink where a bank of filters is arranged. The water passes first through a string filter and then a UV lamp to kill bacteria like campylobacter, after which it is stored in a header tank in the attic. Water for drinking passes directly from the UV lamp to an activated carbon filter.

The pump is activated by a float switch in the header tank, or (for drinking water) by a pressure vessel in the pipework.

The rainwater harvesting system featured as a case study in a publication on water conservation in buildings.

Heating the water

On days with a few or more hours of sunshine water in the hot water tank is heated by a coil within a solar absorber system. Effectively this means that water is largely heated by the sun from April to October, although even in midwinter a sunny day will raise the temperature by a few degrees. In winter we rely on the Rayburn to heat the water – using the sun’s energy in a solid form. There is an electric immersion heater fitted for emergency use, when we need hot water within half an hour.

These arrangements mean we have a specialised hot water tank ordered through a solar equipment supplier – basically it is large, with two large heating coils, with a maximum surface area for efficient heat exchange. The lower coil is connected to the solar system, the upper to the Rayburn. Cold feed is in at the base from the header tank, hot water and separate shower pipes out at the top. The underfloor heating circuit is connected to the primary Rayburn loop.

The solar absorbers are made by Filsol. Technically they are halfway between the classic black radiator and the highly efficient (and expensive) evacuated tubes. Water passes through a thin ‘pillow’ of steel coated in special paint to absorb a large proportion of the solar energy. We bought two panels, each 2 m2 in area. (We were recommended 1 m2 per person.) I built an insulated frame from 2 x 4 timber, ply, expanded polystyrene and toughened glass, which was integrated into the roof construction. There is an electronic sensor which detects when the temperature difference between the water in the tank and that in the absorber is > 4°C and switches on a pump to circulate water around the solar circuit. This water also contains antifreeze to prevent damage in the winter.

Dealing with waste

In order to save water and to reduce the volume of waste water needing to soak away (percolation into the clay-rich soil here is slow, particularly in winter) we opted at an early stage for a compost toilet, although it wasn’t until after the blockwork chamber was built that we had the good fortune to meet Nick Grant and Mark Moody of Elemental Solutions. With the blessing of Building Control they built us a ‘Dowmus’ system, which at the time was still experimental. It involves collecting all toilet waste and greywater by gravity into a chamber about 3m x 1.5m x 1.2m. The chamber is waterproofed.

There are two toilets which open into the roof of the chamber. The toilet waste and greywater from bath, basins, sink, shower and washing machine fall onto a layer of peat which acts as a filter. Into this layer are added ‘tiger’ worms to break down the waste. The liquid passes through a fine plastic mesh into the base layer of broken plastic pallets and from there through a drain into a pump chamber. A submersible pump pumps the greywater at pressure through a 1” black alkathene pipe to a drain field away from the house. Ideally gravity could do this but we don’t quite have the height. A fan draws air from the bathroom through the toilet bowl into the chamber and out through a vent which extends above the eaves. This serves the purpose of satisfying the ventilation regulations for bathrooms and also keeps the bathroom odour-free.

The toilet bowl in the bathroom is imported from Australia, where the ‘Dowmus’ concept was developed. It is simply a cylinder, flanged at the base, positioned over a 14” diameter plastic chute which extends into the chamber. The toilet in the shower room is a dual low-flush (4 litre/1 litre) ‘Ifo’ from Sweden. This second toilet needed to be a W.C. to avoid problems of differing air pressures in the two rooms.

The waste system has worked well. The only maintenance required is to add an occasional scoop of sawdust to keep the waste pile open and accessible to worms, and to keep the carbon:nitrogen ratio balanced, to rake the peak and spread the decomposing waste every few months, and annually remove a barrow-load of compost for the fruit trees.

Problems occur when there is a power cut, as without the fan odours from the chamber enter the bathroom, necessitating wrapping the toilet bowl with an airtight sack. Loss of power also resulted in the second toilet not refilling after a flush as the water came directly from the pump, avoiding the filters and header tank. Perverse as it may seem, for this reason we now have the W.C. connected to the mains.

We try to avoid waste as much as possible and recycle what we can:

- Vegetable peelings -sheep

- Table scraps and stale bread – chickens

- Cooked meat and fish scraps -‘Dowmus’ chamber

- Garden waste/animal litter – compost bins

- Prunings – once a year bonfire

- Paper and cardboard rubbish – Rayburn

- Magazines, cardboard, glass, metal & some plastic – council site

- Ashes – chicken house litter and fruit tree fertiliser

Balancing the books

In order to spend as much time as possible in our home we have aimed to reduce the need to earn by reducing expenditure. We were fortunate to have had the capital from two modest properties and from family to invest into the project, and were also lucky to buy at a reasonable price. Added to that, doing half the work ourselves and using reclaimed materials where possible has resulted in our having a low mortgage. The energy-saving measures incorporated into the building and the food-growing have helped to produce lower bills. We each work away from home for half a week – vehicle costs are still too high – but we are developing our craft interests in the workshop.

A child’s view

An interview with Adam, aged 8.

Did you enjoy life in the caravan?

It was alright except for the leaking roof. We got a wet carpet. The caravan was also very cold.

How cold was it?

Not quite freezing but not warm at all.

When were you cold?

I was cold at night and all day long in winter. My bed was at the very back of the caravan on the right.

What do you remember about building the barn?

We were watching the barn being built out of Rosie’s window. I can remember putting in the underfloor heating. There were loads of pipes. They were all curly and went round in a pattern like a brain, or a victorian judge’s wig.

Do you remember the digger?

It was a JCB and it was digging our foundations. It came in through the fence and started digging the floor in the barn.

Scrubbing the post was hard work. You needed a scrubbing brush and soapy water.

Did you help in any other way?

We rolled the Rayburn down the left hand side of the track and then crossed over and put it in place on a higher flagstone than the rest. We were rolling it down the track on black plastic rollers and every time a roller came out of the back you had to grab it and put it round the front. This barn reminds me of the seaside because you know boats sail on the sea, once I saw a fishing boat come to shore and it had planks of wood with a dent in the middle and they had to do the same as the rollers to get the boat up to shore – but they had a machine pulling the boat instead of it being pushed up because it was so heavy.

The water tank was made out of cement shaped as a big tank under the ground. There is a metal cover so you can get in if you need to and water stays in and is pumped to the house.

It was fun when Rosie was sleeping in the same bedroom as me because the beds weren’t too far apart and we put blankets across and balanced the edge of each edge and pretended it was a hammock for our cuddlies.

The hollow ash was hollow and you normally find Easter eggs in there or sometimes you just find a wrapper. Once I crawled in and found it very hard to crawl out again. I got out by being pulled. It hurt but I got out in the end.

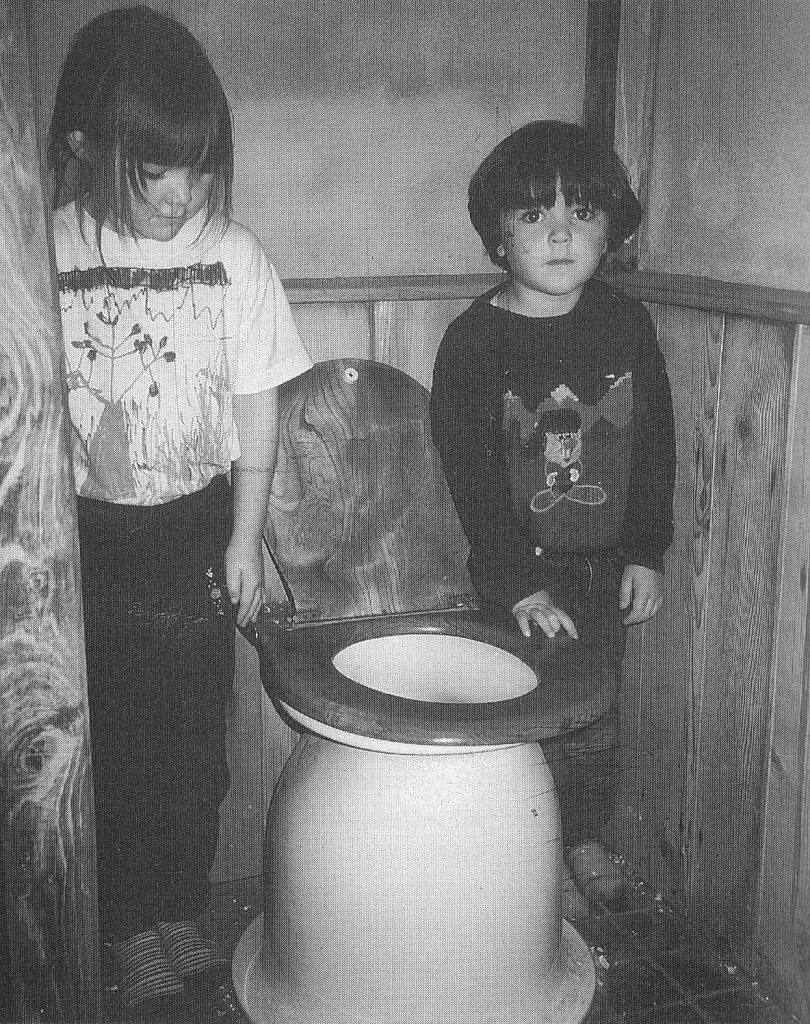

The toilet was made in the same way as the water tank but but didn’t have the metal bit on top, but it had a bridge over it and the metal bit was much bigger and went from the ground to touch the bridge. You open it by unscrewing some screws and letting it drop on the ground. There is a special rake that you rake all the sewage down level and eventually it all goes into compost. I had my photo taken by the toilet with my sister. The photo was put in a book called Herefordshire Privies. In the photo we are standing each side of the toilet and the lid is open. I showed it to my teacher and she got me to show it to my class. My teacher said we were being kinder to the world than people with water toilets.

I enjoy living here because it is countryside and it’s quiet, not like towns or cities. There is lots of land to play in and we have got a huge vegetable garden that is a rectangle and there is a small semicircle on one end which is for flowers. There is a big playing area out the front that is big enough to have a game of tennis and there’s a slope down where it is also big enough to have tennis. Once we made a water-slide down the slope and it was great fun going down on the surfboard. We had a hosepipe going to the top of the water-slide and it was great and the water collected at the bottom and got rather full so we pulled two bales out and the water drained away.

Was it worth it?

It is now eight years since we first saw the barn and I can’t quite believe that the dream we had is now a reality. We have a home in one of the last tranquil parts of Britain and I relish the peace every morning. The children make dens, play in the pond, collect grasses, snails and worms and help harvest apples from the orchard. We eat our meals by a window with a view into Wales, with a sky that changes hourly according to the weather and a landscape that varies with the season, time of day and light. The food on the table is often home-grown. The water we drink and wash in is collected on the roof, heated by the sun in the summer and by the Rayburn in the winter, using fuel cut and stacked (and therefore appreciated) by the family. Our waste is recycled or re-used through the compost toilet, the compost bins, the chickens, the Rayburn or the ‘civic amenity site’ in Monmouth, apart from the obstinate single sack of largely plastic rubbish left for the dustmen each week.

The building is well-insulated and warm, renovated with low-energy materials to the best of our knowledge at the time. It includes many reclaimed and local materials. Wood is mainly oak and the doors home-made.

We live a fairly simple life within the constraints of a growing family, spending as much time as we can enjoying the home we have created.

So much for the positive gain. What had it cost us? Three years in a caravan was not the hardship most people assume it was. Most people in the world, I guess, have worse living conditions. However, the project was a huge commitment in terms of time, energy and money. I missed a lot of time with my growing children, and I developed no other interests. Once we were in my work-rate dropped, and I felt tired for much of the time. Trying to combine the project with a demanding teaching post was hard.

According to this crude balance sheet, as much as you can compare like with unlike, the decision for us was right. Nothing is gained without pain. Challenges and risks are character-building, they say. I feel older, certainly. Wiser? Possibly. But we must also add the potential we now have for the future:

- Skills developed in joinery may be able to produce some income

- Space to build a studio or overspill accommodation to replace the caravan

- Space to build workshops for our craft interests (my woodwork, Clare’s stained glass, Rosie’s possible potting and Adam’s idea of blacksmithing)

We were successful, but to reach this stage needed hard work, commitment, support of family and a truckload of luck.

2001

Addendum:

Ten years later

In 2006 a new, improved workshop was built, for woodwork projects, most recently for the construction of shepherds’ huts.

A few years ago we were fortunate to be able to buy some adjoining land, giving us a total of eight acres. This allowed us to plant that longed-for woodland which occupies four acres and which in a few years will begin to supply our firewood. The rest of the land has been planted with standard orchard trees, mainly apples, from which we should gain a certain income by selling juice. Of course the extra land necessitated the purchase of a 1960 MF35.

Somehow the gardening is still not producing all our vegetable needs, and I still haven’t found the time to finish the pointing.

2011

Addendum 2

It is now nearly thirty years since we first found the barn which became our home. There have inevitably been many changes, some good, some bad, and it seems like a good time to document them.

✅ Our woodland grows

The woodland has put on extraordinary growth to the point where we are now coppicing it on a nominal 12-year cycle. There have been setbacks such as ash dieback affecting most of the ash we planted, and overwhelming stands of giant bramble, but keeping warm each winter from our own firewood is a dream come true. We handle the firewood as little as possible:

- The felled tree is snagged and then cut into logs which are carried the short distance to the chopping block.

- After splitting the logs are thrown into an IBC cage. The tractor moves the full cage to a woodland clearing where the wood dries throughout the warmer months under a corrugated iron roof.

- During late autumn and winter the cages are moved by tractor to the log shed where the firewood is stacked.

- The firewood is carried as needed into the house in a bucket.

- The logs are then placed in the stoves.

✅ Hollow Ash Huts

Together with friends Charles and Catherine we created the business ‘Hollow Ash Huts’ and between 2010 and 2017 we made 38 huts and delivered them all over the country.

✅ Hollow Ash Shepherd Hut Holidays

We bought two of the huts ourselves to set up a glamping business.

✅ House extension

The reclaimed tiles on the shallow pitched roof over the extension was starting to show frost damage so we made the decision to replace them with slate. We also took the opportunity to add a laundry at one end (to facilitate the ‘Holidays’ washing) and a porch at the other end.

✅Kitchen

The kitchen/dining area has been renovated with new slate worktops (reclaimed snooker tables), cupboards and drawers, electric oven and induction hob, dishwasher and sink.

✅ Solar PVs

In a last-minute dash before the government reduced the Feed-in tariff we managed to get 16 photovoltaic panels installed on a hastily built structure.

❎ Garden

Unfortunately this resulted in much of the vegetable garden being covered by the PVs ‘temporarily’ until a potting shed is constructed to take the panels. 11 years and waiting!

❎Water

For various reasons (the tank leaking, the filters being a chore to change, complicated plumbing and piped water being so cheap) we are not using the rainwater harvesting system. We miss the taste of unchlorinated water. We have vague plans to use the tank to store rainwater to use in the garden as we are getting more hot and dry seasons.

✅ Wwoofers

As we wear out and slow down we have benefitted from the energy and enthusiasm of ‘wwoofers‘ who give their time in exchange for food and accommodation.

2022